Opponents of additional federal aid to state and local governments have noted that overall state revenue declines have not been as bad as expected during the pandemic, thus the need for assistance has lessened. This is too simplistic an argument. While some states have enjoyed better than expected revenues, other states have not. And local governments have suffered even more.

At the same time, all units of governments have had to spend significantly more to respond to the pandemic. Overall, state and local governments have cut more than 1.3 million jobs, over 5 percent of their pre-pandemic workforce.

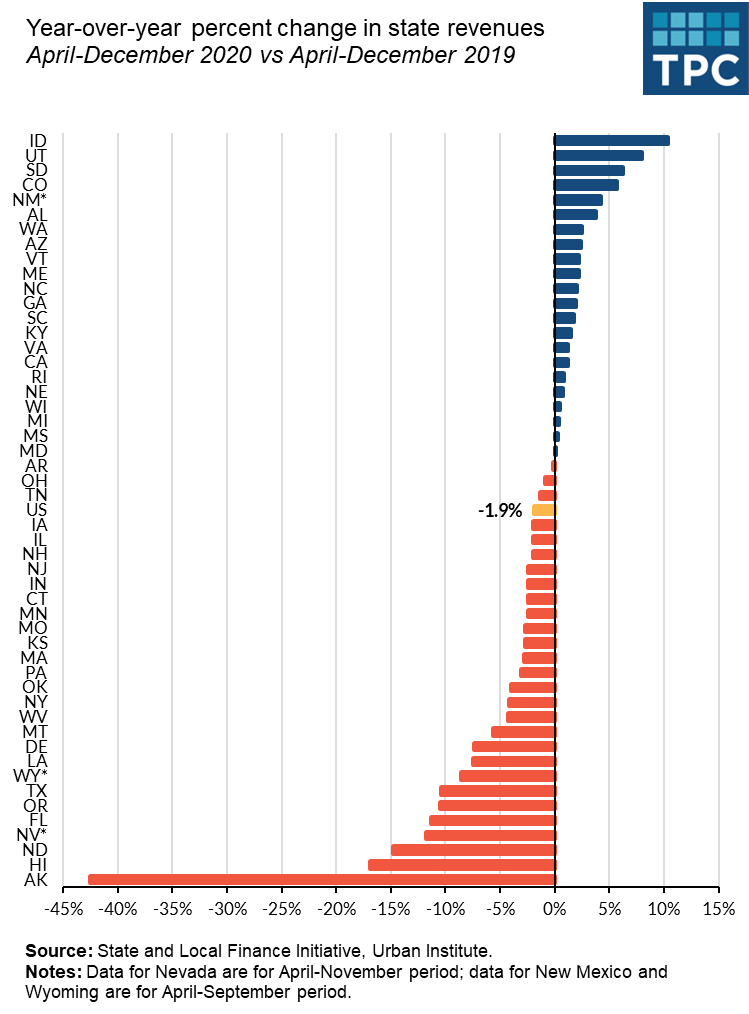

State revenues varied dramatically across states

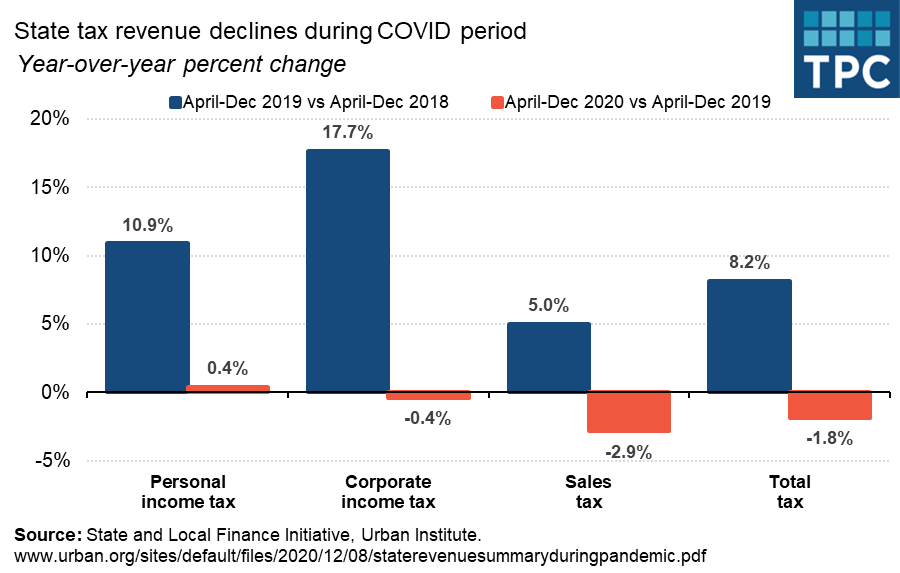

Preliminary data collected by the Urban Institute’s State and Local Finance Initiative show total state tax revenues declined by only 1.8 percent from April to December 2020 compared with the same period in 2019. But revenues remain below 2019 levels. And there is wide variation among states.

Those who did best include states that have progressive income taxes, those that tax groceries, and those that enacted tax rate increases for fiscal year 2020. States with these characteristics saw some growth in overall tax revenues.

However, 28 states reported declines in overall state tax collections during this period, with seven reporting double-digit declines. The steepest were in states with a relatively high reliance on services and tourism or fossil fuel production, or those that rely heavily on sales tax revenues and do not have an income tax.

Personal income tax revenues increased compared to the 2019 period by 0.4 percent while sales tax revenue declined by 2.9 percent. Actual collections have been stronger than forecasts last Spring, but remain far below pre-pandemic predictions.

While personal income tax revenues grew, it was largely due to one state. California collected one-third of these revenues nationwide. It got a big bump in December due to tax withholding that accompanied large year-end bonuses, investments in successful initial public offerings such as AirBnB, and estimated taxes from strong 2020 stock market growth. Excluding California, overall personal income tax revenues declined 0.6 percent compared to a year earlier, and 21 states collected less than in the prior year.

The $600 weekly federal supplement to unemployment benefits also likely boosted state income tax revenues in the states that tax these benefits.

There was similar variation in state sales tax revenues, with 21 states reporting declines and 24 states reporting growth during the April through December 2020 period.

While we have less data on local government revenue, it appears they have been hurt far more than states due to their reliance on different revenue sources. For example, only 13 states allow local governments to levy an income tax while 37 states permit local sales taxes.

Local governments also are more likely to rely on taxes or fees on hotel stays and restaurant meals, which have declined sharply during the pandemic. Property taxes were still owed, but were delayed in some places.

New York City, for example, is facing a $10.5 billion revenue shortage in fiscal years 2020-2022, along with a projected $5.9 billion increase in COVID-19 related spending, according to the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget. New York State has also indicated that they may cut local aid if there is not additional federal money, meaning a reduction of upto $4 billion for New York City. This is often the pattern – where without federal countercyclical support state shortfalls translate to local pain.

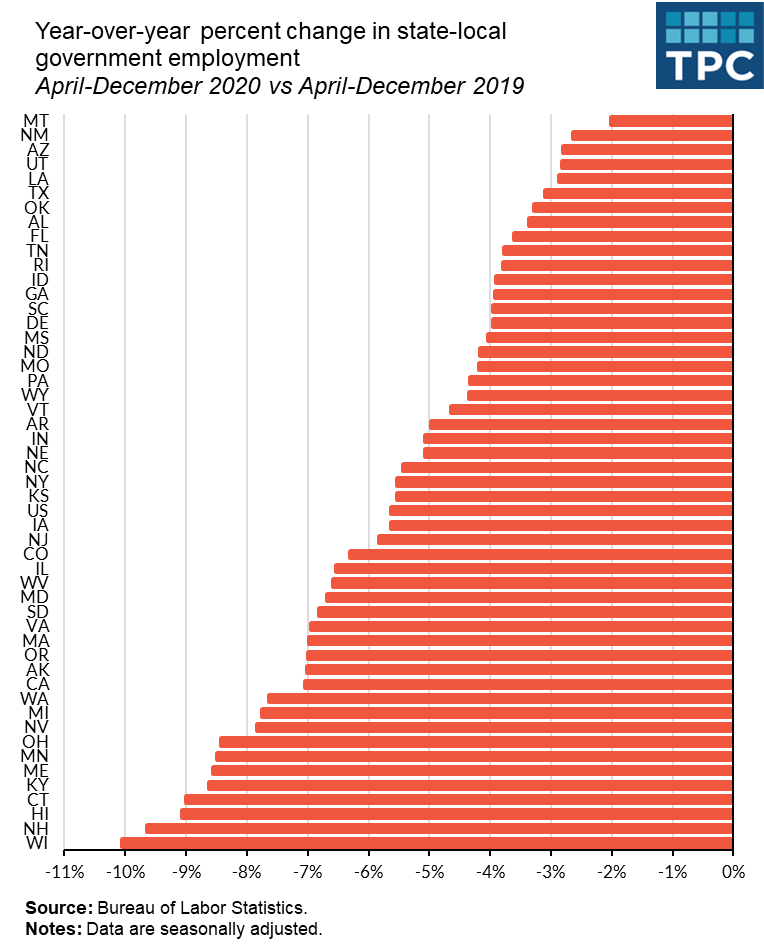

Public sector employment may highlight local revenue challenges

While we don’t have comprehensive local revenue data, patterns in local government employment provide indications of continued fiscal stress. State and local employment remains depressed even as state revenues improved. Many of those job cuts were in education, both at the state and local levels.

State and local government employment fell in all 50 states compared to the same period in 2019, largely driven by local declines. And the lack of a consistent relationship between job cuts at the state level and the local level can indicate different fiscal circumstances. For example, while California state revenues increased slightly, state public employment declined by 4.6 percent and local government employment fell by 7.8 percent.

The need for data-driven state and local aid

One reason for the current heated debate over how to design federal aid to state and local governments is this lack of comprehensive local revenue data. President Biden’s American Rescue Plan includes $350 billion in direct aid to state and local governments. Under the proposal, state governments would receive $195.3 billion while local governments would receive $130.2 billion, and territories and tribes would get $24.5 billion.

The state funds would include $25.5 billion divided equally across the states and District of Columbia while $169 billion would be distributed based on unemployment. Half of the local funds will be distributed based on population and the other half based on a modified Community Development Block Grant formula.

While unemployment and local grant formulas may not be the best proxy for need, they recognize that economic conditions are an important driver of fiscal need. Wide variations exist among the states in revenues, overall economic growth, and public sector employment, as well as unemployment rates. Using these factors could help fine-tune federal assistance and better target aid.

But whatever the formula, the absence of state and local assistance would hinder the nation’s economic recovery.